Into the “Pit” or upon the “Clouds”: Kensho and Satori Moments in the Development of Number Concept

It’s Sunday morning and as I soap up greasy dishes, I hear Susan Engel say on the Heinemann Podcast:

One of the things that I think that our schools have unwittingly done is ignored all the processes that kids use at home and try to replace those with a set of formal procedures that aren’t always as effective…. But it’s a shame because while we are busy trying to sort of force these somewhat formal kinds of learning beacause we think they are more “efficent” or “high powered”, we waste a lot of the natural learning skills that students have. And often a lot of the natural teaching skills that grown-ups have.

Huh, I think I know what she is talking about. Whether we are teaching a genre or the scientific process, teachers are constantly “telling” kids what to pay attention to and to think about. When I start examining my current practice and reflecting on Who I am as a teacher, I have come to see my role as a provocateur and coach. I am always considering who is REALLY doing the learning in our classrooms?–is it me, or is it the students?

So I am constantly asking myself that question because I know that “the person who does the work, does the learning“. But when I say “work”, I mean thinking, and there are so many of these micro-moments in our classroom in which I have a chance to tell kids what to do or to ask them what they think they should do to approach a situation or problem. Sometimes these moments of learning are Kensho, growth through pain, and other times it is Satori, growth through inspiration. I first encountered this term when I read this blog and Kensho immediately reminded me of our teacher-term, the learning pit. You need determination and resilience to get out of that pit and your reward is Kensho. However, we rarely talk about it’s opposite, Satori. Up until this morning, I didn’t think we had a name for Satori in education. It Kensho is the “learning pit” than Satori must be up in the “clouds”, having a clear view and understanding. But Susan Engel articulated best in the podcast:

There are certain kinds of development that children undergo that are internal and very complex and they don’t happen bit by bit. They happen in what seem to be moments of great transformation of the whole system. ……

At that point, I stopped and turned toward my device. I recognized exactly what she was talking about it. I observed it the other day. My ears perked up some more as I moved closer to listen:

When children are little, their idea of number is very tied up with the appearance of things. So, this is a famous example from Jean-Pierre, a line of 10 pebbles to them is a different quantity than a circle of 10 pebbles, because lines and circles look so different.

The idea that it’s 10, whether it’s a circle or it’s straight, is not accessible to them. At a certain point, virtually every typically developing child, no matter where they’re growing up, acquires this sense that the absolute number of something stays the same no matter what it looks like. Whether it’s a heap or a straight line or a circle, that may sound like a tiny discovery, but it’s the beginning of a whole new way of experiencing the abstract characteristics of the number world.

You can’t teach that through a series of lessons. That’s an internal, qualitative transformation that children go through. Once they’ve gone through that, there are all kinds of specific things that you can teach them about the nature of counting and number and quantity.

Yes! I totally know what she is explaining. I was a witness to it. And perhaps, when you reflect on these Zen philosophical terms as development milestones, you may make a connection to your own classroom learning.

Here’s a snapshot from a recent example in our Grade 1.

Some context

There’s a math coach that I love, Christina Tondevold. She always says that “number sense isn’t taught, it’s caught”. I’m always thinking to myself, how can I get them to “catch” it. This past week, we did just that using the Visible Thinking Routine, Claim, Support, Question making the claim:

The order of the numbers don’t matter–12 or 21, it’s the same number.

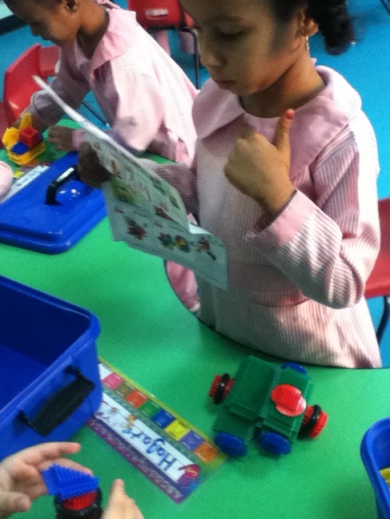

The students took a stand, literally, in the corners next to the words and image for Agree or Disagree, with I Don’t Know, in the middle. This was great formative data! Then we provided the students with a variety of “math tools” to Support or prove their thinking is correct. They had to “build” the numbers and show us that they were actually different. It was neat how the students who stood in the I Don’t Know and Disagree areas were developing an understanding of what a written number truly “looks like”. We didn’t jump in and save them at any point, but some of them were experiencing Kensho. It was painful because they didn’t know how to organize their tiles or counters or shapes or beads in such a way that they could “see” the difference between the 2 numbers. Meanwhile, the students who chose the unifix cubes were experiencing Satori- and it became very obvious to them that these were different numbers.

In our next lesson, we introduced the ten frames as a tool to help them organize their thinking and develop a sense of pattern when it comes to number concept. We did the same two numbers: 12 and 21, and they could work this time with a partner. Oh man, was there a lot of great discussions that came out as they talked about how the numbers looked visually different. The concept of Base 10 started to emerge. As observers, documenting their thinking, it was exciting to see the connections they were making. But the best part was yet to come.

We then brought in the Question part of the thinking routine. We asked them “if the order of 1 and 2 matters to 12 and 21, then what other numbers matter?” They told us:

“13 and 31, 14 and 41, 24 and 42, 46 and 64, 19 and 91, 103 and 310.”

A Hot Mess of Learning

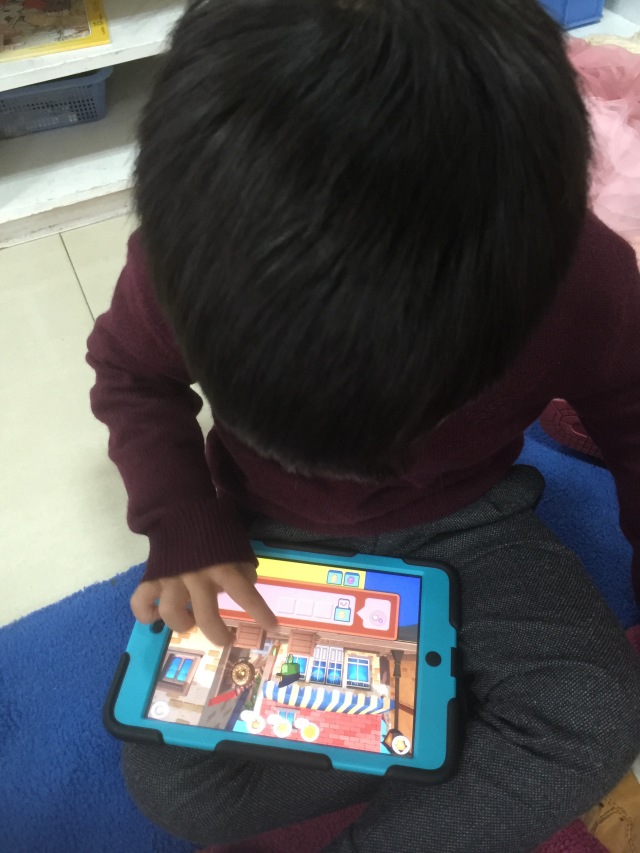

Once unleashed, the kids grouped up and flocked to resources. There was a buzz. Giving students choices allowed the opportunity to choose whether they wanted to stay with smaller numbers or shoot for the BIG numbers even if they had no idea how they might construct a number past 100. They could use any math tool they wanted: cubes, blocks, 10 frames, Base 10 blocks, number lines, counters, peg boards–anything they wanted. Those choices, of itself, really provided some great data.

Here is an example of one of the groups who went with lower numbers:

But the ones who went for the BIG numbers, were the most interesting to watch because they were Kensho. Most of them grabbed unifix cubes, thinking that the same strategy they used before with 12 and 21 would work with 103 and 310.  Oh man, they persisted, they tried, but it took a lot of questioning and patience on our part to help guide them out of the pain that their learning was experiencing. Only one group naturally gravitated toward the Base-10 blocks, and when they realized how the units worked, it was a moment of Satori. They moved on from 103 and 310 quickly; they tried other numbers and invented new combinations. And interestingly enough, those groups, at no point, looked over to the ones engaged in the struggle to suggest that they might try another math tool. It was as if they knew that when one is in Kensho, best to leave them alone to make meaning on their own.

Oh man, they persisted, they tried, but it took a lot of questioning and patience on our part to help guide them out of the pain that their learning was experiencing. Only one group naturally gravitated toward the Base-10 blocks, and when they realized how the units worked, it was a moment of Satori. They moved on from 103 and 310 quickly; they tried other numbers and invented new combinations. And interestingly enough, those groups, at no point, looked over to the ones engaged in the struggle to suggest that they might try another math tool. It was as if they knew that when one is in Kensho, best to leave them alone to make meaning on their own.

And there we were, in the midst of this math inquiry, and we felt like exhausted sherpas but satisfied that we were able to let them choose their own path of learning and made it to their “summit”.

As I consider how the role of the teacher is evolving in education, I think it is recognizing these moments of pain and insight in learning, and guiding them towards the next understanding in their learning progression. I absolutely agree with Susan Engel that when we see children fumbling around, we should be asking if they are within reach, developmentally, to even acquire the knowledge of skill that we are working on. For me, inquiry-based learning is the BEST way in which we can observe, engage assess our learners to truly discover their perceptions and capabilities. It is through capturing the student conversations and ideas that emerge as they give birth to a new understanding that is the most exciting to watch and inspires me in our planning of provocations that lead to their next steps.

How about you?

Developing learners as leaders is my joy! I am committed and passionate International Baccaluearate (IB) educator who loves cracking jokes, jumping on trampolines and reading books. When I’m not playing Minecraft with my daughter, I work on empowering others in order to create a future that works for everyone.